My father’s life always amazed me. Whenever I thought about him, I thought of a young man of 21 on a big ship, coming to a country where he didn’t know anyone. He once told me that when he first entered his room on the ship, he found two rabbis sitting there – his roommates for the 5-day voyage. He immediately ran out, found the purser, and begged to be moved. He thought the rabbis would tear him apart. It was 1951 and he was coming from Germany, a country still dealing with the aftermath of a war it had started and perpetuated in the name of evil. It made me sad to think of him being so scared: after all, he was just a child of 9 when the war started and a young teen of 15 when it ended. Nothing that had happened was his fault. But I understood his fear. He was so alone – no one else from his family was emigrating to Canada with him. His father had arranged for him to meet a Catholic priest from Rivière des Prairies, a then rural town on the eastern edge of Montreal. His father wanted him to leave Germany. He told him there was nothing left in the devastated country for a young man of his intelligence and spirit of adventure. My father had trained as a farmer and this priest was going to help him find work on one of the many farms in Quebec that needed the help.

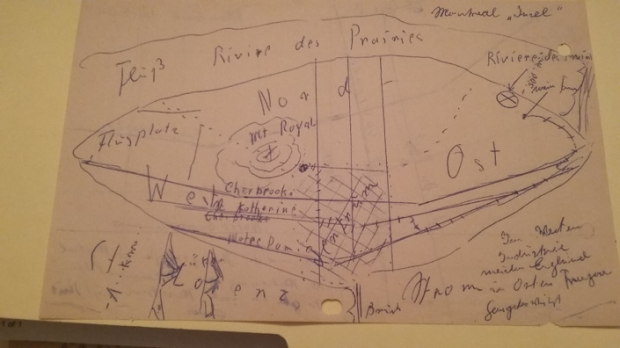

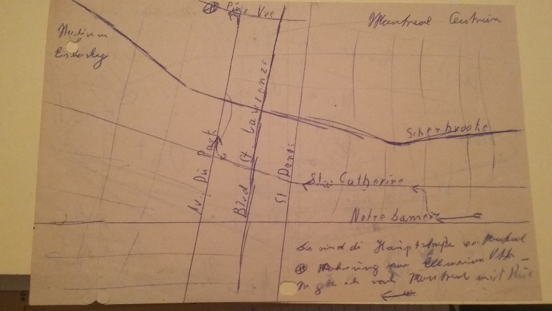

In my father’s papers, I found a hand-drawn map of the island of Montreal. It is crude. The island itself has the shape of a football and dissecting it in half is Saint-Katherine Street, spelled with the German K. In the far west corner he has written Flugplatz, to identify Dorval Airport. Cutting it in half vertically is Blvd St. Lawrenz, the street which separates east and west in this town and has such symbolic importance to Montrealers. He has identified the “Lorenz” (Saint-Lawrence River) to the south and Mount Royal is marked by 3 circles with a cross in the middle. (How, I wonder, did he know about the cross atop our city’s mountain.) He even identified the train tracks along the south border of the island that would take him into Central Station. I have no idea if he made the map before leaving Germany, or on the ship, or even once he’d arrived. But when I look at it, it tells me that he was trying get his bearings in his new city, possibly before arriving. He’s trying to understand the city and ground himself in it, as if by drawing it he could somehow own it and embrace it. He must also have hoped the city would embrace him. The map suggests a kind of fear – fear of getting lost, of not knowing how to get to RDP, which is also marked in the far eastern tip of the city, where the priest, his gateway to the new world, would be waiting.

Of all the papers I found after his death, this hand-drawn map is the most precious. My dad and I shared a love of maps, of travel, of adventure. We had a big blue Atlas in our house and I remember hoisting it onto my lap as a child and looking at the world, often with him. But there’s no way I could ever imagine doing what he did at such a young age. Leaving everything and everyone you know and starting over again in a new place takes a type of courage few of us have. I think he missed Germany all his life, even though he felt out of place when he went back to visit. I think he always felt a bit out of place here too, even though he loved Kanada and never identified as German but as Canadian. Hyphenation was not for him. I think a big part of him remained on the ship, drifting between the two worlds and it gave him an aura of difference which always intrigued me.

Of course, I am glad he was able to take the journey because it led him to my mother and consequently to me and my siblings and then to all our amazing children and grandchildren. I believe he never regretted it either. He was not given to regret. He was a look-ahead type of person, opinionated but shy, friendly but somewhat awkward with people all at once, often angry and railing at the politics of the world, but optimistic at the same time. I suppose he’d seen so much destruction as a child and knew that life could still be beautiful. He also wasn’t given to huge displays of affection, but in his dying days he held our hands so tightly and told us again and again how much he loved us. Then he lamented that we always wait too long to speak what’s in our hearts.

The priest never showed up that day back in June of 1951. My father waited and waited at the train station in Montreal, where he had disembarked from the Halifax train. It turned out the priest was busy with his secret lover, who I suppose was more alluring than a skinny German immigrant. Abandoned and alone, my father sought shelter at the Salvation Army, which helped him find a placement in a farm in the Eastern Townships where, apparently, he was very poorly treated. He had to share a bowl and eating utensils with another foreign worker, a man from Poland. Eventually he met Farmer Brown, a round jolly man, who took him in and treated him like family. He worked very happily for him for a few years until he returned to Montreal to become an electrician, eventually meeting my mother.

I never knew about the map. I found it totally by surprise. But now I take it out and look at it often. It is more than geography to me – it is like the map of his mind, of his hopes, his fears, and his dreams. It is the map that tied him to us and us to him. I’ll treasure it forever.

This is indeed a treasure – wonderful post. I think your dad would be proud of his daughter.

LikeLike

what an interesting view of life of your father!

LikeLike

what an interesting view of life of your father….

LikeLike

“Using ideas as my map..” …Robert Zimmerman (My Back Pages )

LikeLike